The role of bonds in an inflationary environment

With inflation hitting a 30-year high in the UK and interest rates on the rise, do bonds still have a role to play for income investors?

Bond investors enjoyed a prosperous decade in the period after the global financial crisis, as low inflation and low interest rates combined with the central bank policy of quantitative easing meant prices rose almost regardless of what was happening in the wider world.

But as the globe exits the pandemic, inflation and interest rates appear to be on an upward march, and bond prices have started to fall.

In such a climate, what role can bonds play in a balanced portfolio, and where are the opportunities in different types of bonds?

This guide will explore those questions and comes with an indicative 30 minutes of CPD.

Advisers start to flee bonds on rate fears

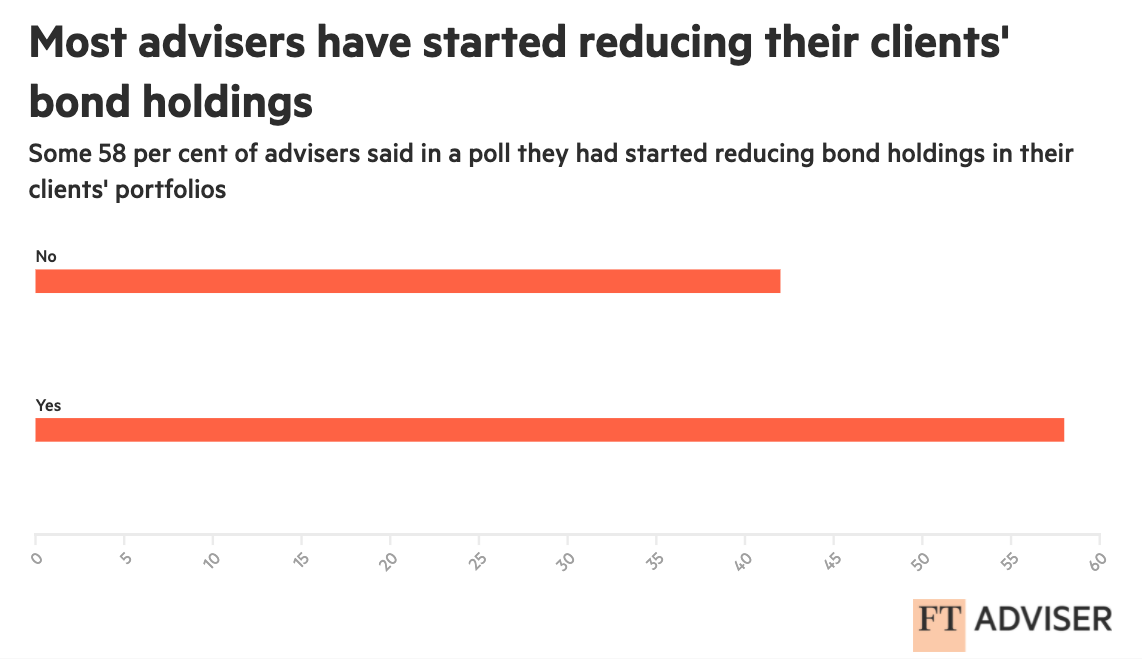

The latest FTAdviser poll shows a sharply negative shift in adviser sentiment towards bonds, as inflation and interest rate fears move front and centre of advisers' thoughts.

The poll, which was conducted via Twitter, shows that 58 per cent of advisers have started to reduce their clients' bond exposure.

Bond yields have been rising in recent months on fears that inflation will be persistent and thus the fixed income from bonds will be eroded.

When bond yields rise, the price of the bond falls.

Central banks have started to respond to higher inflation by putting interest rates up, which increases the returns available on cash, and on bonds issued in the future, and reduces the appeal of many bonds currently in the market.

And at the riskier end of the bond spectrum, that is those bonds rated as high yield, prices sell off both because the yield on lower risk bonds is rising so investors can access that (in bond terminology the 'spread is narrowing'), but also because higher inflation may limit the ability of the riskier companies to generate the cash needed to repay the debt.

The economic conditions of 2021 – where rates were low, inflation was low and economic growth was present – were ideal for high-yield bonds, but the present higher inflation, lower growth environment is probably the opposite.

The role of bonds in an inflationary environment

The base rate increase in December, and expectation for inflation to peak at around 6 per cent in April, raises a question over the role of bonds and highlights the inverse relationship between bond prices and interest rates, as well as prices and yields.

Generally speaking, bond prices fall when interest rates rise, with lower prices meaning higher yields.

“Bond yields are nowhere near inflation,” says James Barton, CEO of wealth management business Featherstone Partners. “Their capital value will erode as interest rates rise [and] as interest rates start to creep up, we will see a sell-off in bonds.”

December saw the base rate increase to 0.25 per cent, and bond markets are pricing for further rate hikes according to David Roberts, head of the Liontrust Global Fixed Income team.

“But the risk is the Bank of England is even more aggressive [in terms of the pace and scale of rate rises] and gilt investors take more of a pasting as prices fall much further than they have,” he adds.

“The bond market currently expects another three rate hikes from the BoE, with the base rate reaching 1 per cent in a year’s time.

The risk is the Bank of England is even more aggressive

“If expectation changes and more hikes are seen as likely, then bond prices are likely to fall significantly more than they have.”

Paul Angell, senior investment research analyst at Square Mile Investment Consulting and Research, also says that if a central bank “surprises” markets with a rate rise and investors become convinced that more rises will follow, bonds should sell off as investors anticipate income streams of future debt to be more attractive than the current stock.

When bond yields rise, the price of the bond is falling.

Quantitative easing

In December, policymakers at the central bank voted to maintain the stock of sterling non-financial investment-grade corporate bond purchases at £20bn, and to maintain the stock of UK government bond purchases at £875bn.

This means that as some of the bonds in the portfolio the bank has bought via its QE programme mature, they are replaced, so the overall stock does not fall. This impacts the wider bond market as it means the central bank is still buying bonds, which helps keep prices higher.

If the central bank wanted to tighten monetary policy by use of a method other than raising interest rates, it could sell existing bonds, which would force yields upwards, or not replace the existing bonds as they mature, which would have the same impact on yields but in a much more moderate way.

Central banks have been large buyers of bonds under QE, keeping the yields low and prices high, says Philip Matthews, co-portfolio manager at Wise Funds, an investment management business.

Roberts at Liontrust says that QE has distorted valuations in the bond market, with QE (and therefore central bank action) having a much greater impact on bond prices than the traditional fundamentals such as inflation or wider economic conditions. This is because central banks are not economic buyers, that is, they do not buy the assets because they think they have economic value, and pay any price.

But as central banks taper their QE programmes, Roberts feels the more traditional measures of bond market value will become important once again.

While it is the impact on government bond prices that has the greatest ripple effect through wider investment markets, there are a range of other options within the fixed income universe that investors can access in the name of diversification, according to Simon Prior, bond fund manager at Premier Miton

“Developed market government bonds, emerging market corporate credit, floating rate asset-backed securities and inflation-linked bonds: these different parts of the bond market can be used to ensure a portfolio has a good income component and can help protect against inflation.”

Angell at Square Mile likewise highlights areas of the bond market that offer some protection against inflation.

“The capital and income returns of inflation-linked government bonds are tied to inflation rates, therefore their value should rise with inflation rates, all other things being equal.

“Additionally, the value of floating rate bonds increases with interest rate rises. They should therefore also provide some investor protection in an inflationary, and therefore rising interest rate, environment.”

Now is probably not a great time to invest in a traditional bond benchmark

As Simon Matthews, managing director at NB Global Monthly Income fund, further explains: “During times when the central banks are raising policy/base rates to fight inflation for example, returns of bonds or loans that are floating rate and lower duration will fare much better than those that are fixed rate and longer/higher duration.

“This was the case in 2021 and we would expect similar trends in 2022 and 2023.”

Indeed, Gareth Witcomb, portfolio manager in the multi-asset solutions team at JPMorgan Asset Management, points to very low levels of government bond duration in the portfolio.

“Now is probably not a great time to invest in a traditional bond benchmark,” says Andres Sanchez Balcazar, head of global bonds at Pictet Asset Management. “Those benchmarks have long durations, so a lot of sensitivity to interest rates, which are likely to continue to go up, and that will reduce the price of the bonds you hold.”

For advisers, investing in a bond benchmark means buying a passive fund.

Meanwhile Roger Webb, deputy head of sterling credit and aggregate at Abrdn, raises the point of high yield (sub-investment grade) bonds.

“I think there are environments where high yield, which is much more closely correlated with equities than with government bonds, actually does reasonably well in some of those environments where inflation is rising and economies are doing quite well, as long as policy rates don’t go too far.”

High-yield bonds are those which have a credit rating of below BBB, bonds with a credit rating above BBB are called investment grade.

Webb adds: “Inflation is typically bad for fixed rate bonds, but there are areas of bond markets where you can see value, which include high yield.”

Matthew Henly, portfolio manager at Invesco, likewise says the impact of higher inflation on different parts of the bond market is more nuanced than just that higher interest rates set by central banks make bond prices fall, as the impact is different on different parts of the market.

“What we have seen in the last year to year and a half is yields moving higher, largely because inflation expectations have moved higher. That environment is a more negative environment for, at a high level, bonds versus equities.

“But also within fixed income, it’s more negative for government bonds versus corporate bonds. And within corporate bonds, it’s more negative for the higher quality bonds versus the more equity-sensitive type bonds.”

Henly adds: “The takeaway is that it’s always a little bit more nuanced than ‘central banks are increasing policy rates, therefore avoid bonds at all costs’ or ‘yields are moving higher, therefore you don’t want to be in fixed income’. It’s a little bit more nuanced than that.”

Chloe Cheung is a features writer at FTAdviser

Ignore everything you have been told about bonds and inflation

Inflation is back, and that makes bond investors anxious – but should they be? Consumer price inflation in the US hit 7 per cent in December; in the UK it reached a 30-year peak of 5.4 per cent; and prices globally are rising more rapidly than at any time since 2008, according to the World Bank.

Investment lore tells us that inflation spells trouble for fixed income assets. Bonds are generally expected to offer a moderate-to-low return. When inflation is high the likelihood of bonds outstripping it is low.

That makes bonds less appealing. Their allure is further tarnished because inflation also tends to lead to higher interest rates, making 'risk-free' cash seem a more acceptable alternative. This weakens demand for bonds and erodes the market value of any you hold. So goes the traditional narrative.

Understanding the complex relationship between fixed interest assets and inflation presents an intellectual assault course for most investors. Flopping over the finishing line, the natural instinct may be to dump your bonds.

The problem with received wisdom is that it does not always bear scrutiny. You still have to invest your money somewhere – and if not in bonds then where? History suggests that inflation is actually a plague on all our houses, no matter which asset class we may hold.

What is the alternative?

Figure 1 underlines the point. It shows the real returns delivered by a range of asset classes – both conventional and alternative – between 2010 and 2020.

Figure 1: Inflation is a plague on all houses

Source: Barclays Gilt Equity Study, Bloomberg, St Louis Fed, Hagerty, www.liv-ex.com, Trustnet as at December 31 2020

The data for alternative assets is not as robust as it is for mainstream investments, and lots of factors affect price. Similarly, house price growth varies depending on where you live and the kind of house. So it is possible to challenge this chart, but I hope the central message is clear.

The truth is that most investments struggle to match inflation, particularly over the short term. But bonds have actually done well – and this in a period that started with bond guru Bill Gross describing British government bonds as “resting on a bed of nitroglycerin”. Since then we have seen repeated predictions of a reverse in the bull market for bonds. The asset class continues to deliver.

The data on cash is particularly revealing. Even during a period when inflation was consistently low, investors in cash lost out significantly in real terms. Those numbers offer a cautionary tale for anyone tempted to sell fixed income assets and sit in cash.

Remember, too, that not all bonds are the same. As strategic and tactical bond fund managers, we have the freedom to invest in a wide range of fixed income assets, according to our views on the current market environment and the opportunity set.

Opportunities in bonds

Some might point to index-linked gilts, which offer an income directly linked to inflation. The downside to these is that they typically have a lot more duration, which is detrimental in this environment, and are currently trading on ferociously expensive levels because the demand for inflation protection is so high.

To be agnostic between a 10-year gilt and a 10-year index-linked gilt you would require inflation to exceed 4 per cent for each of the next 10 years. Yet UK RPI has averaged just 2.8 per cent a year since 1997 when the Bank of England gained operational independence over monetary policy. We believe there is better money to be made from shorting index-linked gilts.

The most attractive area of the fixed income market in the current environment is arguably high-yield bonds. These tend to prove more robust in the face of rising prices and interest rate increases. With careful stock picking we can mitigate default risk. We can also reduce duration, which helps right now because the yield curve is inverted.

In other words, a good tactical bond manager has tools to help mitigate the short-term problem of inflation. And we believe it is a short-term problem. The fact that 10-year gilt yields in the UK are holding firm at around 1.1 per cent tells you that the bond market sees this as a temporary phenomenon too.

So where do investors go from here? I would suggest that if you are invested in a good tactical bond fund then the answer is nowhere. And here is the final reason why. By the time the average investor has concluded that inflation could be a problem for the bond market, the market has already priced it in. So it is too late to respond.

You are more at risk of exiting just before the market picks up.

You may not beat inflation in the short term, but history suggests you will in the long term. This is still an attractive asset class to be in.

Next time someone tells you to dump bonds when inflation rises, ask them where you should put your money instead. Silver bullets simply do not exist.

Stephen Snowden is head of fixed income at Artemis Investment Management